We take it for granted that all bottles of wine will come with corks, but we shouldn’t be so sure. I mean, corks don’t grow on trees, right?! Wait, do they?

Fun fact: they actually grow off of trees.

Cork is the thick bark of a tree called the Quercus suber. Students of Latin might know that quercus is the generic name for “oak tree” and suber designates the species, cork oak.

The Portuguese word for the cork tree is “sobreiro” which best reflects that, but I’m guessing suber is related to the Latin word for “pride” (superbia).

In other words, this tree is the pride of the oak family, and I can see why. It’s glorious. It also doesn’t take much to see that the Latin quercus is also where we get the word “cork”!

Extreme Patience

The cork tree grows mostly around the rim of the Mediterranean and, within that arc, predominantly in Portugal, as you can see from the map below. Its mild Mediterranean climate, rich soil, and relative social stability makes Portugal the prime location for growing cork trees. About a quarter of Portugal’s forested land (1.6 million acres) is made up of cork forests. The Portuguese are serious about their corks.

I can’t think of a greater model of long-term fruit bearing than the humble and beautiful cork tree. The emphasis here is on “long-term” as we’ll see.

Cork is not a fruit, of course. The cork tree, being an oak, has its own type of acorns. But cork is the product of a tree that exists to divest itself solely for the good of humanity.

The word “patience” in our title applies to this tree in an extreme way, meaning that if you planted a cork tree today, you would not be able to see your first good harvest of cork until—believe it or not—2075. Yes, fifty years.

Some estimates say it “only” takes 33 years to produce a good harvest. That may be true in some places, but it’s kind of splitting hairs if you ask me. When we think of cork trees we literally must think in decades, not years.

The Process

Cork growing and harvesting is a fascinating process. One year you decide to put a cork tree acorn in the ground, and then you have to wait fifteen years before you can even take your first load of bark off the tree. And be prepared for disappointment.

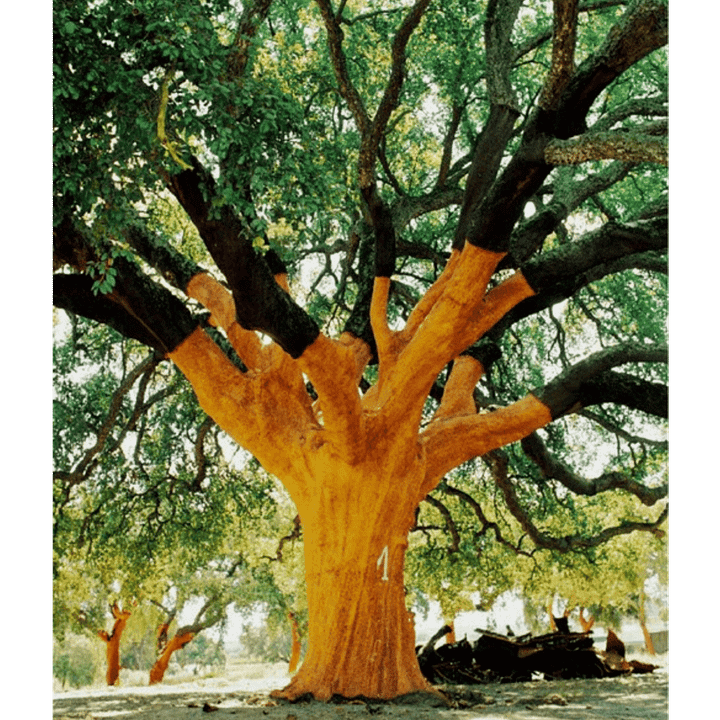

The bark of this young tree is of low quality and essentially unusable for bottle corks, but you need to strip the tree anyway so it will grow more bark and mature as a tree. The tree, when denuded of its clothing, shows a beautiful bright orange color which is probably unique in the tree world (see image below).

Then make sure you find a few things to keep you busy while you wait another nine to twelve years for the next growth of bark from the same tree.

Lo and behold, some nine years later the new crop is now ready to harvest, but this one, too, is essentially useless for bottle corks. It’s too rough. It can be used commercially, though, for building products such as insulation and flooring, maybe even a few dart boards. Yet, like the first harvest, you have to remove it from the tree so that the good stuff will grow in its place—a decade later.

Meanwhile, since you put the seed in the ground you’ve gone to college, gotten married, raised a family, and can show your grandchildren the cork tree you planted even before their parents were born.

Finally!

Another decade hence, you find yourself in the cork sweet spot. NOW, a biblical generation later, your beloved Quercus suber is ready to give you some incredibly thick, resilient, smooth-textured cork hidden under a mass of forbidding-looking bark.

You’re amazed at how generous this tree is and how easily it gives you its bark (as you’ll see in the short video below). What an incredible harvest!

The first person to cut down a cork tree must have been shocked to see that he had to cut through three or four inches of a rubbery substance before he even got to the wood. I’m sure that was quite a surprise.

The Whistler Cork Oak

In this massive work of natural art called the Whistler, you have the world’s largest and oldest cork tree. Apparently it gets its name from the singing of all the birds who nest in its branches. It “resides” about fifty miles east of Lisbon in a grove of cork trees. (The tree here is the same as the first picture above.)

Here are a few quick facts about the Whistler Tree:

It was planted in 1783—just after the American Revolution! That makes it 242 years old—in fact, most cork trees live more than 200 years.

It stands more than 50 feet tall and its trunk measures 14 feet in circumference, wow.

It’s been harvested more than 20 times in its long life.

Its harvest in 1991 was the largest ever recorded, yielding a massive 2,656 lbs. of cork—more than 100,000 corks for wine bottles! Compare that with the average cork tree that produces about 100 lbs. per harvest.

Well, an article like this can’t go on forever—alas! I wish I were as patient as the cork tree harvesters because there’s so much more that could be said about the Whistler.

It is another one of nature’s precious sacred windows. In fact, it is a mirror of God’s generosity and patience that teaches us that good things come to those who wait.

The next time you open a bottle of wine with a real cork, stop and think of the Whistler Tree. Who knows? You may be using something he gave you out of his two centuries of lavish generosity. Like God, he bears fruit in the long term and just keeps on giving.

-----

The Process of Harvesting Cork Bark

Photo Credits: Via Wikimedia: Map (Giovanni Caudullo); Rough bark (Daderot); Whistler 1 (Bixintxo); Whistler 2 and 3 (União da Floresta Mediterrânic); Harvested Orange Whistler (Josh Malin); Feature: Squirrel via Pixabay.

Amazing fact. I've seen trees bare like these and never thought about corks. I thought they were just being denuded by destructive individuals.

I still have my cork for my wine kept it safe for reuse.

Thanks for this information.