No, I am not referring to the one that just took place. That one was rather mild and uber-boring if you ask me.

I like a little drama with my conclaves. Not the awful Hollywood type, as in the recent slanderous movie of the same name, but real colorful, knock-down-drag-‘em-out ecclesiastical drama.

For starters, let’s dispense with the notion that the conclaves have always been an orderly, peaceful transition of power from one Successor of Peter to another, like the one we just witnessed. Even a cursory reading of Church history should dispel that illusion. I’m just going to take the worst case scenario.

The 1000-day conclave

Technically, the longest conclave in history lasted approximately 1,006 days, or two years and nine months (from sometime in November of 1268 to September 1, 1271). It took place in the Italian city of Viterbo.

The reason it was in Viterbo and not the Vatican is that the Sistine Chapel hadn’t been built yet, so it was customary at the time to hold the papal conclave in the place where the previous pope had died.

Here’s a thumbnail sketch of the flavor of ecclesiastical theater that appeals to my church senses:

Two main factions dominated the conclave, with at least six sub-factions and numerous other sub-sub-factions;

The French faction was backed by Duke Charles of Anjou, the brother of King St. Louis IX who went on two crusades. His Majesty was probably the responsible one in the family. His brother the Duke had too much time on his hands and was fond of meddling in church politics.

The second group was the Italian faction, backed by the powerful Orsini family.

That latter faction is not to be confused with the powerful Annibalde family sub-faction, represented in the conclave by Cardinal Carlo Annibalde who also should not be confused with his cousin, Archbishop Annibale Annibalde, who—my Vatican informants tell me—was snuck in there to sow confusion. (Facebook fact-checkers are verifying this as we speak.)

Twenty cardinal-electors entered the conclave in 1268 but only 17 came out alive. One other didn’t even show up (and no one knows why). Maybe he had a divine revelation that it was going to last a thousand days and didn’t want to waste a good three years of his life. Who could blame him?

In between the frustrating negotiations, the cardinals wanted to elect an actual holy churchman (such as St. Philip Benizi, head of the Servite order at the time or the great St. Bonaventure, head of the Franciscans).

St. Phillip Benizi had gone to Viterbo, it is said, for the purpose of admonishing the cardinals to get their act together (!), but he soon had to flee the city in order to avoid being elected by force. “Hey, look! Old Filippo just showed up for pranzo. Let’s make him pope!”

In all, it took 137 ballots to get a new pope. Wow! I told you the four votes of the recent conclave were boring in comparison.

And then they elected a man who was not even a priest. More on that below.

The disciplinary measures

You may have heard of the infamous conclave where the people of the city got so annoyed at the lack of a new pope that they locked the cardinals in a room and restricted their diet to bread and water for several months as a way to pressure them to get on with business. Yes, that was this one.

In late 1269, after numerous deadlocks and failed attempts to break them, someone decided it would be a good idea to tear the roof off the papal palace in which the cardinals were meeting. The old pope was dead, so there was essentially no opposition to this unique efficiency idea. (The medieval version of DOGE.)

The local prefect (mayor) of Viterbo approved of the measure because he too was antsy for a new pope while the cardinals dithered and politicked. He was also the one who held the key to the roofless room until the cardinals should produce a pope, so he had some clout.

A Spanish Cardinal, John of Toledo, also thought it was a good thing that the roof was removed, “…or else the Holy Ghost will never get at us", he said. His words are the first documented reference to the Holy Spirit as the guiding force in the selection of a pope. Apparently, the idea had not occurred to anyone in the previous 1,268 years.

A crusader for pope

Teobaldo was a man of his age. He was from a noble family and had established himself as a career servant of Church and State. He spent time in the courts of Italy, England, France, and Belgium and had met or known all the great saints and powerful men of the day, particularly, Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, and seemingly, quite a few hungry cardinals.

He was also familiar with all the Italian, French, and English nobility. At various times he served as both a secular ambassador and a papal legate. By all accounts, he had the reputation of being a holy man.

Why it took the cardinals over two and a half years to settle on a guy of this caliber is a mystery hidden in the eternal depths of the Holy Spirit’s Wisdom.

As the crow flies, Israel is 1,400 miles from Rome, which we can easily traverse in an airplane in several hours today. But Teobaldo was living in the Middle Ages, so it took him nearly three months to reach Viterbo where he was formally elected pope but not yet officially inaugurated.

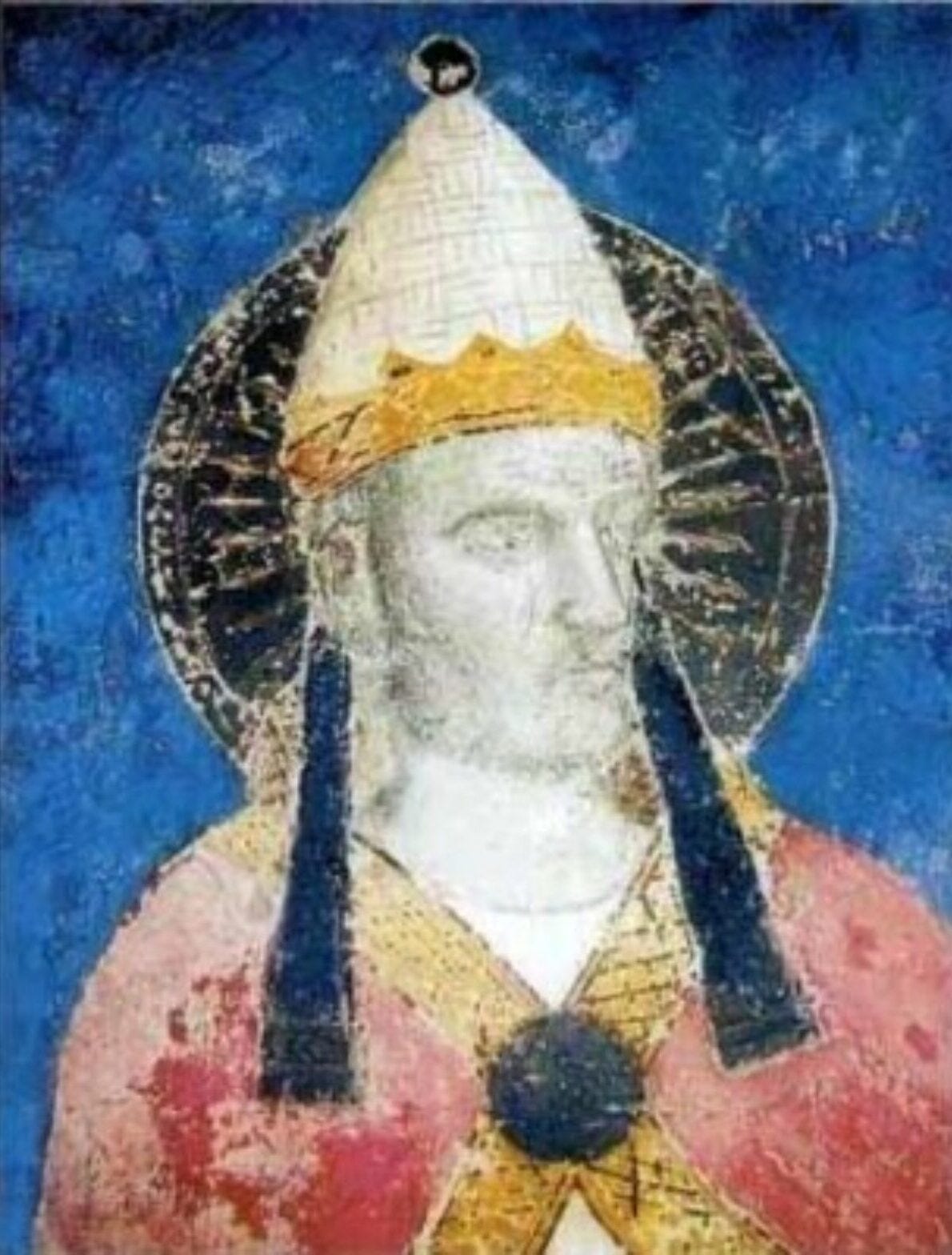

When the pope-elect finally reached Rome, he had to be ordained a priest, consecrated a bishop, and installed as the 183rd Successor of St. Peter. He was the tenth pope to take the name of Gregory.

Pope Gregory X

History holds this crusader pope in great esteem. In just five years as pope:

· He called for a new crusade (which went nowhere—the crusading spirit in Europe was literally exhausted after 208 years);

· He initiated official relations with Kublai Khan and the Mongol Empire (thanks to Marco Polo’s well-traveled family);

· He wrote a pastoral letter condemning blood libel and persecution of the Jews;

· He initiated the process of canonization for the French King Louis IX, who had died in 1270 and whom Teobaldo had joined on crusade.

Oh, and one more thing: perhaps the greatest accomplishment of Pope Gregory’s papacy was a disciplinary document called, in Latin, Ubi periculum, which has echoed down the centuries and is still followed in its essential form to this day.

The Latin title can be literally translated “Where There Is Danger”—an ominous title for a Vatican document, to be sure! But it was entirely appropriate to the subject matter.

My freehand translation of the title might go something like this: “How to Properly Conduct a Papal Conclave Without Wrecking the Church in the Process”.

-----

Photo Credits: Gregory X (public domain); Sistine Chapel (Dr pangloss); White Smoke (David Lees); Viterbo Palace (NikonZ7II); Viterbo Roofless Room (Sailko); Map of Italy (TUBS).

"Did you mean "boring" in the sense that it took only 4 votes and only 2 days to elect a new Pope compared to what happened in Viterbo? Viterbo was a thousand years old compared to the modern times of course. I was actually crying when I saw the white smoke maybe of excitement or was just too emotional for the religious history unfolding on TV .